DRONE ENGINEERING

RAY OF HOPE

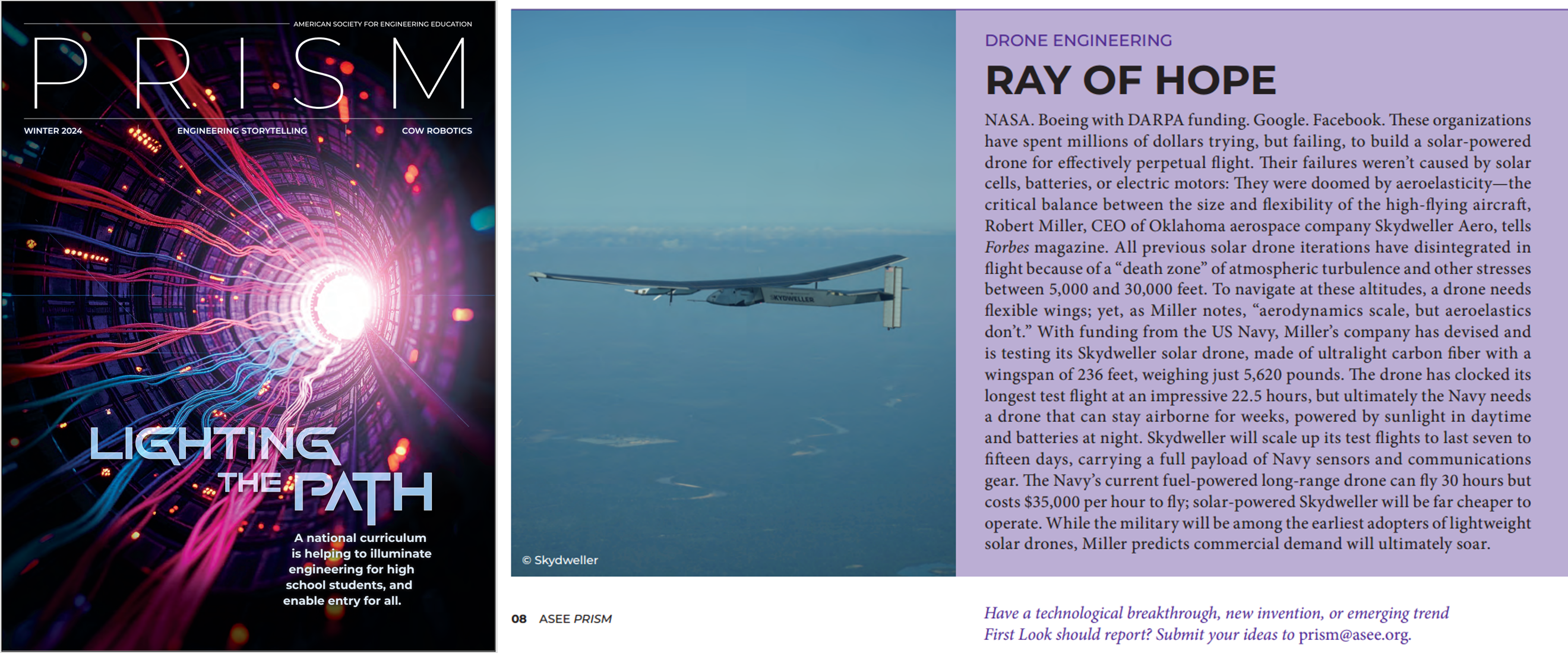

NASA. Boeing with DARPA funding. Google. Facebook. These organizations have spent millions of dollars trying, but failing, to build a solar-powered drone for effectively perpetual flight. Their failures weren’t caused by solar cells, batteries, or electric motors: They were doomed by aeroelasticity—the critical balance between the size and flexibility of the high-flying aircraft, Robert Miller, CEO of Oklahoma aerospace company Skydweller Aero, tells Forbes magazine. All previous solar drone iterations have disintegrated in flight because of a “death zone” of atmospheric turbulence and other stresses between 5,000 and 30,000 feet. To navigate at these altitudes, a drone needs flexible wings; yet, as Miller notes, “aerodynamics scale, but aeroelastics don’t.” With funding from the US Navy, Miller’s company has devised and is testing its Skydweller solar drone, made of ultralight carbon fiber with a wingspan of 236 feet, weighing just 5,620 pounds. The drone has clocked its longest test flight at an impressive 22.5 hours, but ultimately the Navy needs a drone that can stay airborne for weeks, powered by sunlight in daytime and batteries at night. Skydweller will scale up its test flights to last seven to fifteen days, carrying a full payload of Navy sensors and communications gear. The Navy’s current fuel-powered long-range drone can fly 30 hours but costs $35,000 per hour to fly; solar-powered Skydweller will be far cheaper to operate. While the military will be among the earliest adopters of lightweight solar drones, Miller predicts commercial demand will ultimately soar.